Andrew Maughan

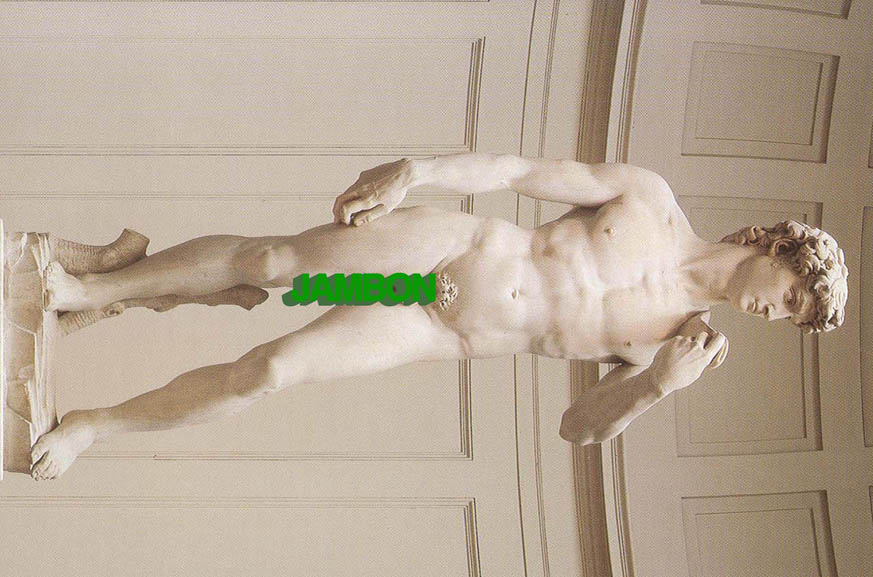

As garish as a pantomime dame, and as hapless as road kill, Andrew Maughan's new series of portraits depicting Bilderberg attendees confront us at the tenuous border between fascination and repulsion. His gaudy – verging on grotesque – pallet of colours, and fast, lacerating brush marks, build up paintings which are almost entirely plastic surface, subsuming (or denying) any suggestion of the subject's personality, humanity, or of an interiority to the work. This specularization, and negation of an interior life, serves a double purpose. On the one hand, Maughan utilizes the frenetic painterly gestures and synthetic colours to obscure the identity of the subjects as a simile for the abstracting, and alienating effects of the esoteric secrecy surrounding the Bilderberg meetings. Whilst on the other hand, he is underlining, with jovial cynicism, the complicity of contemporary art in the entirely material, and vacuous systems of commodity culture.

But hold on, Bilderberg? You may well ask. What is Bilderberg?...Surrounded by police tape, political opacity, and media blackout, Bilderberg is reportedly the most well-protected, unofficial, meeting of the world's elite. Whether a supreme cabal, a political conference, or a bombastic shindig (that the rest of us aren't invited to), what little is known about Bilderberg is that it is an annual get together of the most influential politicians, heads of state and directors of big business in a luxury hotel, beyond the public gaze and democratic accountability. Everything else we know are the morsels gleamed by concerned journalists such as The Guardian's Charlie Skelton, reporting from the periphery of the World's most influential party; from outside hotel lobbies, and secret bolt-holes, whilst pursued by shady goons and government security officers.

Invited to produce this series by Skelton, Maughan shares similar concerns in his practice. With impudent curiosity both men highlight the clandestine operations of social axioms and the ideological bankruptcy of pervasive systems of power and influence. With the deceptive playfulness of an itinerant Art school graduate, Maughan adopts the spontaneous, pseudo-macho gestures and raw, barely mixed colours of modernisms predecessors (such as De Kooning). But he deploys these with the slick, cynical virtuosity of Kippenberger to develop calculated paintings which are simultaneously instantaneous, and highly laboured, as indicated by the accumulated layers of texture and colour, the painted, and re-painted details. There is something jarring about these parallels however, and about the appropriation, the plundering of art history's corpse, which operates in Maughan's larger-than-life canvases... The distorted, liquescent faces of Prince Philip, and Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands, hover like carnivorous monsters above backgrounds reminiscent of pre-school imitations of Rothko colour field paintings. Their flat, plastic, and gaudy appearance hints at the tacky reproductions of 'monumental' art works that can be found in gallery gift shops, and on the walls of living rooms and student's bedrooms as dead signs of cultural appreciation and intellectual prestige. This reference seems to underscore the contradictory, and seedy functions of the contemporary Art world, in which Art is now entirely bound up with the mechanics of consumer desires, and of material culture.

Just as the Heroes of Abstract Expressionism – whose work was intended to be variously reactionary, revolutionary, and spiritual – have their works sold at Christie's for millions of dollars to hang in the homes and collections of the rich, Art is now inevitably subjected to the changing fashions of the Art World, the Art Market, and the capitalist Zeitgeist. Painting has seen a revival in recent years after Saatchi's monumental Triumph of Painting (2005) whether this was a savvy reaction to changing trends, or an innovative move on Charles Saatchi's part , painting was firmly reestablished on the agenda of galleries, art publishing houses, and artists alike.

Andy Maughan's distorted, and fragmentary portraits endlessly obfuscate comfortable certainty. They require the viewer to reconstruct the subjects in their imaginations – with their scratched-out eyes, the grotesque mouths, the dribbles of paint – but this is an impossible task. Identity, and recognition, is never complete. It continually shades off beyond the frenetic marks, and beneath the macabre fleshy colours, in the same way as the subjects do; in their inaccessible, elitist echelons of power.

Iris Aspinall Priest